2015

Reading Books By Their Covers: What 10,000 Mauritanian Manuscripts Tell Us About 350 Years of an Islamic Culture

A lecture by Charles Stewart, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Visiting Scholar at Northwestern University's Institute for the Study of Islamic Thought in Africa.

Date: Tuesday, 17 November, 5pm (Registration required)

Venue: Nihon Room, Pembroke College Cambridge, Trumpington St, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

In December Brill will publish the Arabic Literature of Africa Volume V. This compilation documents 350 years of literary activity by 1875 male and female authors in Mauritania, a Bedouin society which was well isolated from the mainstream, yet reflective of debates within the Islamic heartlands.

This fifth volume in the Arabic Literature of Africa series is, in effect, a narrative of the emergence of an Islamic literary culture. Through an analysis of over 100 private libraries and the contents of the 10,000 manuscripts themselves, the architecture of that literary culture emerges. The blueprint for its development is evident in locally written derivative works in the Islamic disciplines, as well as local commentaries on these works. The Mauritanian manuscript tradition also provides a backdrop for re-thinking the famed Timbuktu scholarship that periodically captures press attention.

Speaker

Charles Stewart is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a Visiting Scholar at Northwestern University's Institute for the Study of Islamic Thought in Africa. Professor Stewart has written widely on Islam in West Africa in the 18th through to the 20th centuries. He is the author of Islam and Social Order in Mauritania: A Case Study from the Nineteenth Century and the founder of the Arabic Manuscript Management System, a bilingual database of over 20,000 Arabic manuscripts from West Africa.

Past Lectures 2015

Deciphering Medieval Libraries of the Islamic World

A lecture by Professor Francois Déroche, Chair in the History of the Qur'an, Text and Transmission at the Collège de France in Paris.

Date: Thursday, 10 September 2015, 18:30 (Registration required)

Venue: Thomas Gray Room, Pembroke College Cambridge, Trumpington St, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

Most of what we know about the libraries which flourished in the Mediaeval Islamic world is based on literary accounts since the collections themselves almost completely disappeared. They have been largely understood as their Western equivalents although the place of the written word in the Islamic tradition should induce us to approach their history with more care. There is actually some evidence left which could help us to understand better the libraries of the Mediaeval Islamic world and to decipher their functions.

Why Did They Not Print Their Books?

Stories about the Reasons Why Printing Was Introduced so Late in the Muslim World

A lecture by Prof Jan Just Witkam, professor emeritus of codicology and palaeography of the Islamic world at the University of Leiden and editor-in-chief of The Islamic Manuscript Association’s Journal of Islamic Manuscripts.

Date: Wednesday, August 5, 2015, 18:30 (Registration required)

Venue: Bender Room, Fifth Floor, Bing Wing, Green Library, Stanford University, California, USA

Places will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. The event is free of charge.

Abstract

The first time that a book in Arabic script was printed by Muslims in an Islamic country was in the year 1727, more than two-and-a-half century after the first Western book that was printed with movable type. This is an unchangeable fact. Historians and others have asked why this could happen, as if history can provide answers. In their research they have come up with explanations that tell more about themselves than about the subject itself. What did they ask? Why are their ideas unsatisfactory? Are some of their ideas phantasies rather than reality? Have Muslims at some point in time really refused to adopt printing as means of transmission of texts? Do these stories come from inside Muslim societies or are they told by relative outsiders? Can trends be discovered in these stories? If printing was not done in the medieval and pre-modern periods, what other means were there for the mass production of Islamic books? These stories, and the questions which they try to answer, are the subject of the lecture. Whether or not there exists an unequivocal answer to the problem of the late introduction of printing in Muslim societies remains to be seen. The stories about the transition period between writing and printing books rather illustrate a fascinating stage in Western thinking about Muslim culture.

The Value of Old Paper

A lecture by Prof Jan Just Witkam, professor emeritus of codicology and palaeography of the Islamic world at the University of Leiden and editor-in-chief of The Islamic Manuscript Association’s Journal of Islamic Manuscripts.

Date: Wednesday, April 22, 2015, 18:30 (Registration required)

Venue: Nabil Boustani Auditorium, American University of Beirut

Places will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. The event is free of charge.

Abstract

Paper is one of the great inventions of mankind. How great in fact, is now mostly forgotten. We just take paper for granted. When more than two thousand years ago the Chinese, to whom we owe this invention, first started to produce and use paper, they had been writing already for several thousands of years, but on less flexible and durable materials: bones, bamboo stalks, stone, metals and ceramic. And they were not the only ones: the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilizations are there to prove it.

The availability of paper suddenly made it possible to register memories of all sorts and also to do that on a grand scale. With paper so much more became possible, because it is a durable medium that is easy and inexpensive to produce, and it could be easily recycled into new paper. In China itself this led to a hausse in book printing: the earliest dated book preserved was produced in China in the year 868. In the Middle East somehow printing was missed as an agent of change, but in the world of Islam paper is no doubt at the basis of the scientific revolution of the 9th and 10th centuries, and the size of Islamic manuscript culture is astounding by any standard. Finally, book printing as it developed in Western Europe since about the middle of the 15th century has irreversibly shaped our outlook on science and literature. Without paper all this would have been unthinkable. At the same time letters and archives preserve innumerable memories of human relationships, both official and personal.

The approaching end of all this has been announced for the past thirty years, as if it were a sort of millennium bug (‘the end of the book as we know it’). Yet there is a ground of truth in this. Far less durable mediums are increasingly taking over the role of paper, and from a triumphant material it is suddenly becoming something of an endangered species. Paper that since the industrial revolution had become a disposable material, made in seemingly inexhaustible quantities, is nowadays becoming a rare commodity in libraries, archives and museums. Attempts to preserve our archives on paper have, for the moment, miserably failed on a world-wide scale.

That brings the question of the value of old paper (if it has any) to the foreground. How can we determine this value, and what is the difference between value and price? Or in other words: do we use our memory in order to retain moments of the past, or is memory in fact the ruthless filter by which most of our history is discarded? The speaker will make an attempt to find his way in the labyrinth of opinions that are available and he will use moments of his own life-long love story with paper as a source of inspiration.

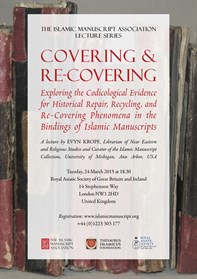

Covering and Re-Covering: Exploring the Codicological Evidence for Historical Repair, Recycling, and Re-Covering Phenomena in the Bindings of Islamic Manuscripts

A lecture by Evyn Kropf, Librarian of Near Eastern and Religious Studies and Curator of the Islamic Manuscript Collection, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

Date: Tuesday, 24 March 2015, 18.30 (Registration required)

Venue: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 14 Stephenson Way, London NW1 2HD, United Kingdom

Description

Much of the history of a book is reflected in its binding. Subject to the whims of users and environments, the binding may evolve a great deal in the life of a book. Damage or even changing owners’ tastes may necessitate restoration, replacement, or other modifications to prolong the book’s use or identify a new owner. Repairs will vary widely depending on the condition, the materials at hand, the taste and skill of the craftsman or layperson, the means of the owner, and even the owner’s personal taste.

A variety of repairs and replacements are attested in the Islamic bookmaking tradition. These range from the scarcely discernible restoration treatments executed by a skilled practitioner to the folk mends executed by an individual owner. The specialist literature in Arabic attests that practitioners gave thought to restoration techniques; in fact, Bakr ibn Ibrahim al-Ishbili (d.1230 or 31 CE) devoted a chapter of his Kitab al-taysir fi sinaʻat al-tasfir to work with worn or damaged codices. In the days of the voracious book collecting of Ottoman and Safavid literati, the need for the restoration of newly acquired books often arose, and various treatments were regularly carried out in the Ottoman palace workshops. Folk mends and replacements employing recycled material may be less attested in the specialist literature, but they are certainly observed in extant specimens. The charm and resourcefulness they display reflects the value of the book to its owner, despite his or her 'humble means'.

While it may be difficult to establish a dating and provenance for a particular binding and its repairs, the investigator with an inclination for forensics may find traces of the original production, the creative reuse and recycling of older materials, wear and damage in the course of use, travel or environmental exposure, and subsequent conservation treatments and repairs. In other cases, there will appear evidence that the original binding was fully replaced, that a decorated cover was overlaid with another cover material, or that a book was newly bound with a much older binding.

Following a brief overview of the current state of knowledge of historical restoration practice in the Islamic context, this lecture will briefly survey creative repairs and replacements in the Islamic bookmaking tradition as they appear in codices of the Islamic manuscript collection at the University of Michigan. Case studies will shed light on the analysis of these phenomena with an eye towards determining the date, provenance, purpose, and materials employed in the treatments, as well as suggesting avenues for future research.

Poster

|

| Download Poster (2.5 MB, PDF) |